Divine Masculine

Lifting the divine masculine, as a necessary aspect of healing and liberation…

Over the past two decades, the divine masculine has been a thread in my work via spirituality, ancestors and the legacies of my freedom fighter heroes. After becoming a mother to two boys, my reflections on this theme have deepened and expanded. I have had to confront and dissect the various ways I, and the collective, have been impacted and harmed by toxic masculinity. But healing doesn’t stop there. It requires that we transcend to remember and embody past examples, living examples, and future possibilities of the divine masculine within each of us and in the collective. To embody sovereignty, equilibrium, harmony, we must accept and balance both feminine and masculine energies in each of us. Writing and painting from my experience and perspective as a cis-hetero woman, I contemplate masculinities as a spectrum within my community, my heroes, my loved ones, and myself. I examine the legacies of trauma running through us and the varied masculinities working to bring a more radical love ethic rooted in healing and liberation. Many of these images appear on other galleries of this site but are featured together here illustrating this thread running through my art.

Browse gallery below to read descriptions. To view slides of each image without captions, click on the thumbnails.

"The Fire Next Time" (Piri Thomas and James Baldwin) 2024. Yasmin Hernandez. Afro.Bori.Libertaria. series. Acrylic on polytab cloth. These two literary giants are featured together as they appear in the library of freedom fighter Filiberto Ojeda Ríos. Piri spoke to youth everywhere through his poetry, his famed novel Down these Mean Streets and other books. Using his own struggles navigating the imposed violence on young black and brown men, his literary work taught the power to be found in claiming self-love and owning one’s own emotions and vulnerability. James Baldwin, as a queer black man who felt safer living outside of the United States, he scrutinized imposed gender norms, toxic masculinity, patriarchy, colonialism and racism. In his Letter to my Nephew he speaks to his 15 year-old namesake offering advice on navigating these very things as a black teen in the US.

Solidaridad en suelo sagrado (Solidarity on Sacred Soil) 2024. Afro.Bori.Libertaria. series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on poly tab cloth. This work depicting mostly Puerto Rican and African American former political prisoners standing before the home of freedom fighter Filiberto Ojeda Ríos is a tribute to their revolutionary solidarity. Watching these brothers, one by one, profess their love for their nations, their people, for this land, for Filiberto and each other, declaring their commitment to liberation via testimonials, poems, tears and hugs was one of the most powerful manifestations of the divine masculine that I have ever witnessed.

"515", 2024 Portraits from the Trench series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic and sequins on black velvet. This double portrait of my son marks his rematriation journey from 5, his age when we arrived to live in Borikén, to 15 years old, his age when I painted this for our tenth anniversary here. It traces his development from boyhood to adolescence with the fierce feminine, protective presence of the angler fish hovering above him.

"Baby Josef as Angler Fish" 2021. Portraits from the Trench series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. This portrait of my youngest son when he was nine, celebrates his playfulness and joy, fusing it with the lamp, glowing fins and filaments of the angler fish. He had been playing with a lamp over his head, pretending to be one. It also subverts the angler's menacing fangs with his falling and growing teeth.

"Luisa Cósmica" 2022. CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. This portrait of Puerto Rican anarcho-feminist, espiritista, writer, lectora, union organizer and more, Luisa Capetillo, shows her wearing the men's clothing she typically wore and for which she was arrested in Cuba in 1914. Luisa penned what is considered the first feminist manifesto in 1911.

"George Floyd Nebula" 2020. Yasmin Hernandez. Color Pencil on black paper. While drawing this portrait of George Floyd, my son who was 8 at the time wanted to know who I was drawing. I explained. Confused and saddened that his life was violently taken, he asked, "Whose belly was he in?” Finding a photo on my phone of George Floyd as a boy in his mother's arms, I held it up to him. "Why would anyone want to kill him as a grown up when he was such a cute boy?," he questioned. My child advocated for George Floyd's humanity, asking to see his mother, declaring him as a "cute boy" still worthy of love and justice as a grown man, connecting him to his source and history.

"El Cucubano Mayor" 2020. CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. This portrait of Puerto Rican Nationalist leader Rafael Cancel Miranda was created the night before he passed. Cucubano Mayor, already working on my series of luminous boricuas, is the first portrait inspired by our brown bioluminescent click-beetle. It honors him as freedom fighter, a kind, loving, guiding presence among his people.

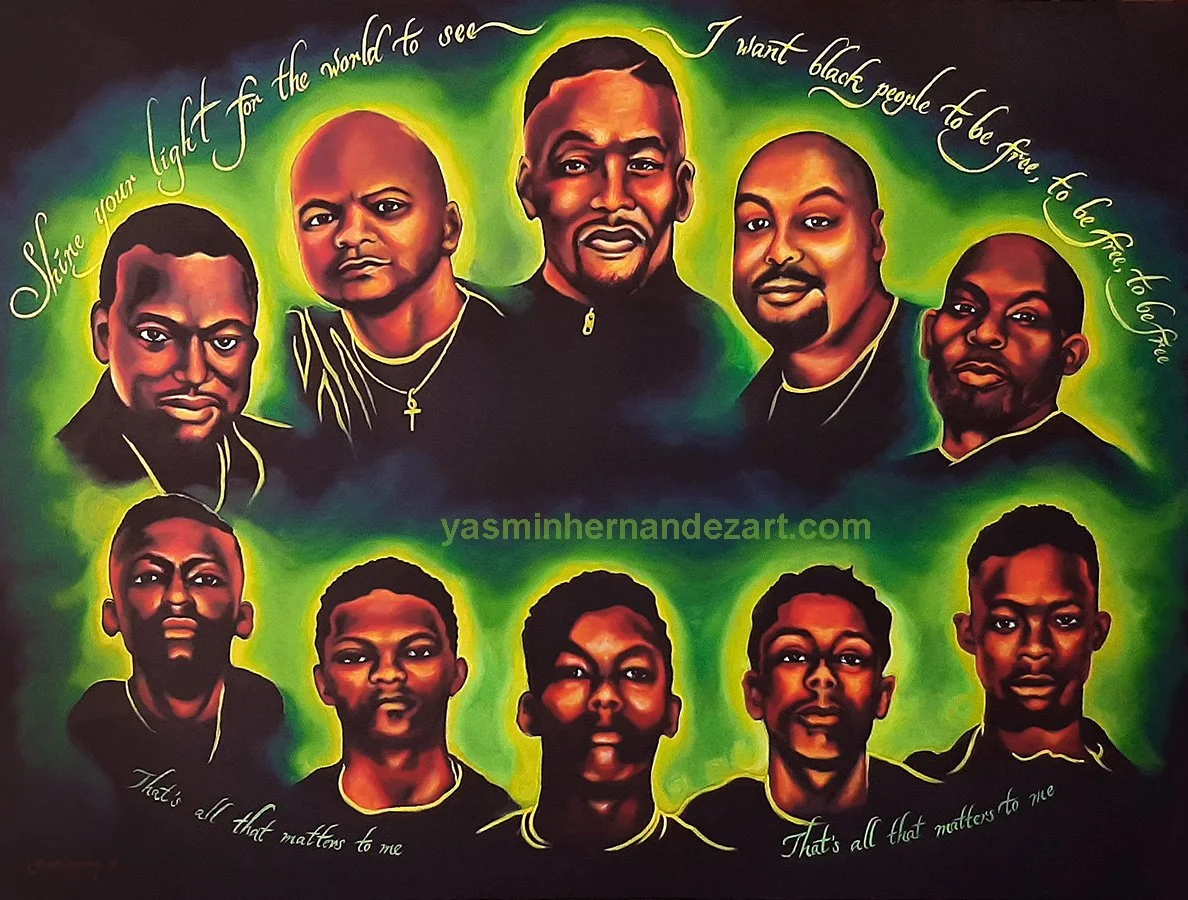

"Shine Your Light", 2019 Yasmin Hernandez. CucubaNación series. Acrylic on canvas This portrait juxtaposes the boys of the so-called "Central Park Five" with their images as men: the Exonerated Five. I was 14 in 1989, same age as several of the boys at the time of their arrest, and was transformed deeply after watching Duvernay’s When They See Us. I painted them shining their light, inspired by fireflies (red heads, black wings with yellow outlines and green glow: colors of black liberation.) It is a commentary on injustice, the stealing of the innocence of black boys, the violation of black men across the planet, and a call to lift the divine masculine. Included is a lyric excerpt from (formerly Mos Def) Yasiin Bey’s "Umi Says": “Shine your light for the world to see…. I want black people to be free, to be free, to be free …. That’s all that matters to me.” This song itself is an expression of the Divine Masculine.

"Amante de la Libertad" (Nina Droz Franco), 2019. CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. This is a portrait of former Puerto Rican political prisoner Nina Droz Franco as a firefly channeling the warrior spirit of the indigenous ancestors of these lands. Nina was arrested at the 2017 May Day protests against the colonial debt and austerity. She was sent to federal prison in Tallahassee, Florida, same city where Ángel Rodríguez Cristobal was imprisoned after being arrested for protesting the Navy in Vieques in 1979. He turned up dead in his prison cell on Veteran’s Day, an event avenged by Los Macheteros. Why do I include Nina here? For unapologetically holding, owning all her energies. For fighting for justice. For being the only woman pallbearer helping to carry our freedom fighter Rafael Cancel Miranda’s casket at his funerary mass in Mayaguez on International Women’s Day, 2020. For, like Julia de Burgos, continuing the legacy “con la tea en la mano.” She is both divine feminine and masculine alike!

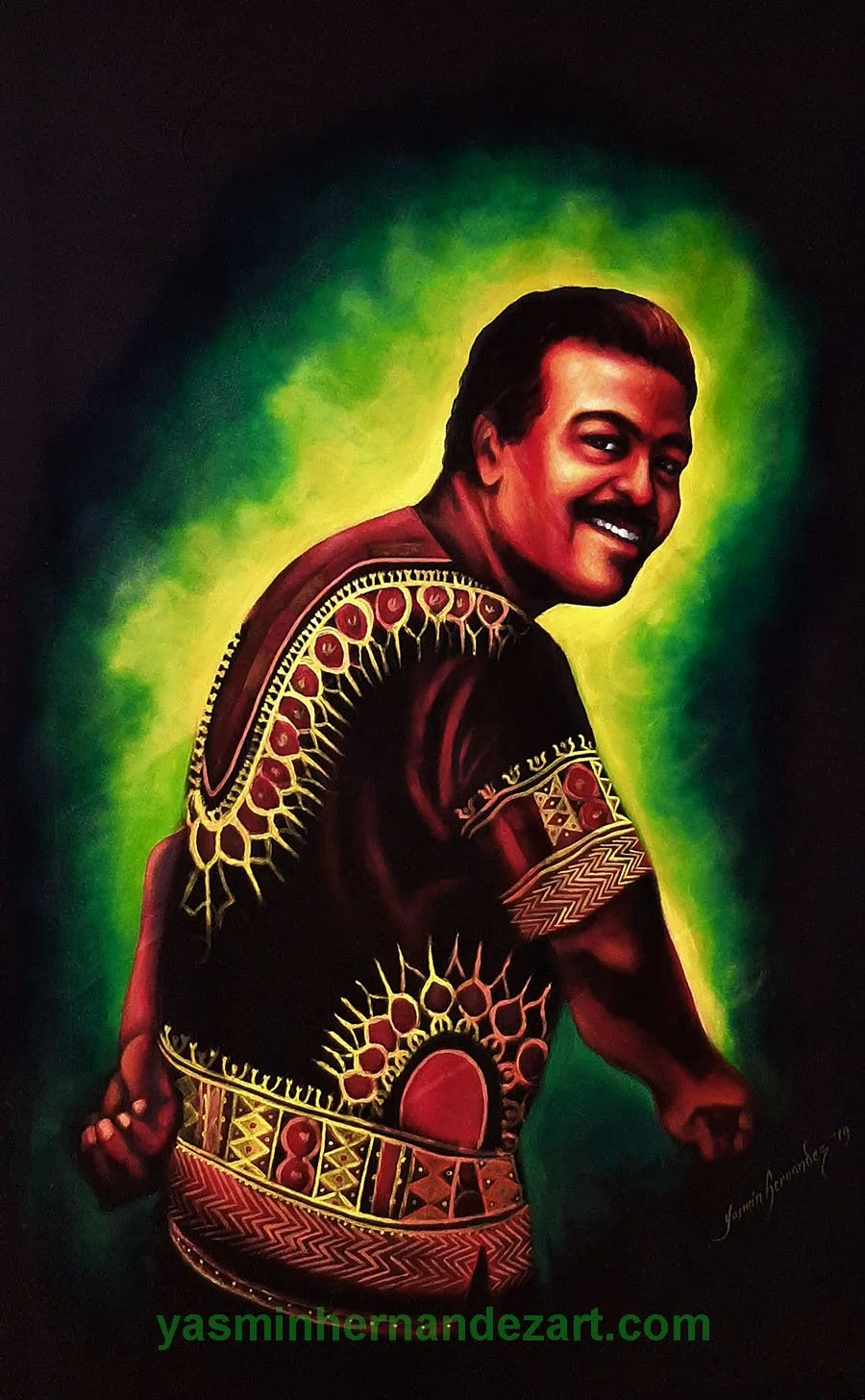

"Fly Papi", 2019 CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on black fabric. Portrait of my father in the 1980s, from my CucubaNación series inspired by fireflies. Red heads, black bodies with yellow outlines and green glows are the colors of the common firefly, colors of black liberation. With this portrait series I affirm Puerto Rico’s place within the African diaspora and resist our continued status as a colony of the US. In my childhood my father was known for rockin’ his dashikis. It was my father who began speaking to me of Puerto Rico’s liberation struggle when I was a teen.

"Bioluminescent Brother", 2019. CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on dark blue fabric. This is my oceanic/ celestial/ bioluminescent B-Boy brother Joseph. We lost him at 43 to Multiple Myeloma, a blood cancer. I finished this painting at precisely the same age (minus a week) that he was when he passed. I first started painting bioluminescence in 2009 for a painting series dedicated to Vieques. He received his cancer diagnosis while I was on a research trip to Vieques in 2008. I painted him alongside the fish that gave him so much peace in his times of battle and the majestic bioluminescence of the waters of our ancestors. My brother was the person who introduced me to art and music as weapons, as medicine.

"Betances Bioluminiscente", 2018 CucubaNación series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. Betances, father of the Puerto Rican Nationality, abolitionist, fought in the French Revolution and authored the Lares Revolution of 1868. As a journalist and novelist, his pen name was el Antillano (the Antillean) describing his work as a physician and commitment to the health of communities in Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, the Virgin Islands and Cuba. I painted him emerging from colonial post-María darkness to anoint and illuminate the Antilles with healing bioluminescent waters flowing from his hands.

"El Regalo de los reyes", 2017 Yasmin Hernandez. Outdoor Mural, Radio Raíces, San Sebastián, Puerto Rico I created this mural to commemorate Oscar Lopez Rivera’s release from prison and return to his hometown after 35 years as a political prisoner of the United States. With his birthday on Three Kings Day, it features Los Tres Reyes or Orion’s Belt in the center with adjacent stars Betelgeuse and Rigel creating red and blue triangular nebulas of the Puerto Rican and Cuban flags. The text is taken from Julia de Burgos’ poem of the same title about our flag. Working with the colors of our flag as references to the oxygen and hydrogen of our waters and bodies, as reflected in nebulas, is my way of transcending past the confines of colonialism, envisioning Boricuas as both bioluminescent and cosmic.

"Eso que llamamos la libertad", Elizam Escobar, 2016. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. Portrait of artist, poet, professor, former Puerto Rican political prisoner, Elizam Escobar. I include a quote I heard during his presentation at a conference: "Eso que llamamos la Libertad no es un estado de ser es una práctica.” (That which we call freedom is not a state of being, it is a practice.) I painted him dressed in a nebula to reference the transcendent liberatory practice embodied by Elizam in his art, actions, and words. Elizam left this plane in January of 2021.

“Nébula: Filiberto Ojeda Ríos”, 2015 Más allá de la luna series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. Filiberto Ojeda Rios, clandestine revolutionary leader assassinated by the FBI at his Hormigueros, Puerto Rico home at the age of 72, orchestrates more liberationist magic from the heavens.

“La transmutación del alma”, 2016 Más allá de la luna series. Yasmin Hernandez. Digital Montage on Paper. Tribute to Puerto Rican liberationist Pedro Albizu Campos, his wife Laura Meneses & their children. The couple met at Harvard where he studied law. Laura was a scientist from Peru. Featuring excerpts of letters he wrote to his daughters from la Princesa prison, 1936, in one he asks "What mystery does water hold that God would choose it as the element for the transmutation of the soul?" These letters are published in Las llamas del aurora, the most comprehensive biography of Don Pedro written by Marisa Rosado. Also included are collaged images of the couple with their children. We usually see images of Albizu the revolutionary but seldom see images in his role as father. When Albizu was imprisoned, Doña Laura continued his struggle, living in México, later adopted by the Cuban Revolution where she passed after a long life advocating for Puerto Rico’s Independence and her husband’s release from prison.

“Nébula: Pedro Albizu Campos” 2015 Más allá de la luna series, Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on black velour. Liberationist Pedro Albizu Campos emerges as a screaming spirit in this piece commemorating the 50th anniversary since his 1965 death. Exactly two months after the assassination of Malcolm X, Albizu passed from cancer caused by radiation experiments he was subjected to while a political prisoner of the US. This anniversary marked a grim time in my move to Puerto Rico, one in which I asked his spirit for the strength to persevere here.

“Fuck Cancer”, 2010 Outlaw Clothesline series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on cotton bandana. This is the first painting of what expanded into a series of works on bandanas that I associated with my brother from his teen “outlaw” days to his cancer battle. “Fuck Cancer” was my brother’s mantra that he would turn into graffiti signs for his room at the Bone Marrow Transplant Unit at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital. I copied one of the signs onto this image using markers from his case that he would carry from home to the hospital. I kept his case of pens and markers that still smells like his cigar smoke. My brother, from his battles as a kid, through the ultimate battle for his life, is my forever reference for divine masculinity. His authentic strength and openness allowed him to share the lessons of his struggles with others, his superpower became alchemizing his wounds and scars into healing light. Ironically, I became much closer to him during his illness, committing to be someone that he could be vulnerable around, which is a difficult task for black men. In his case, it was difficult to give up his perceived duty of taking care of his mother and sisters. He thankfully had a solid community of people of all persuasions that would provide constant support. It was through him that I witnessed the power of love among friends, among people who would have your back no matter what. My whole family benefitted from the love he fostered among friends and perfect strangers, always bringing smiles and healing via his own street-struggles turned salvation.

"Carmelo Cemí", 2009. Bieké Tierra de Valientes series. Yasmin Hernandez. Carmelo Félix Matta was working in St. Croix when he met María Velázquez Rijos. They fell in love and moved to Vieques where he was from, and where her family was from though, she was born and raised on St. Croix. Back in Vieques, needing land to make their home, Carmelo began to clear out appropriated military properties. As other families too needed land for their homes they simply cleared them, “rescatando/ rescuing” these lands from the Navy. Not pleased, the Navy tried to forcibly evict Carmelo, María and their family from their property but, a beekeeper, it was Carmelo’s bees that came to the rescue, descending on the military personnel and driving them off their property. Carmelo’s efforts led to the founding of various communities including Monte Carmelo and Bravos de Boston. Unfortunately, these are some of the most coveted areas affected by gentrification in Vieques today.

“Basta”2009 Bieké: Tierra de Valientes series. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on military tent, Approx 10' x 8'. Chain link fencing, wire cutters and military debris. For this 2009 edition of my Basta installation, the fence is cut down as the people of Vieques did when they cut down the fences demarcating civilian from appropriated US military properties. The US Navy began appropriating Vieques lands in the 1940s to create the Navy base that they used for weapons testing and military training for over 60 years. Yaurel, featured in the painting, was nine years old back when I took the photo that would lead to this painting. His father is an activist that helped take protesters and supplies to the bombing range. His mother is an educator and a leading voice in the continued struggle for peace and justice on Vieques. Today Yaurel is an adult, a judo champion, music artist and most recently the stunt double running with the Puerto Rican Flag in Bad Bunny’s video for “La Mudanza”.

“Albizu Elevao” 2006 Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on Burlap Ay como lo escupieron...Como lo empujaron…Como lo llevaron a crucificar -excerpt from the salsa song "El Todopoderoso" (Oh how they spit on him, how they pushed him, how they took him to crucifixion). This work references the radiation experiments that the US government conducted on the father of Puerto Rican Nationalism Pedro Albizu Campos. These were secretly administered in the form of bright white or multicolored lights that would flash in his cell & in his hospital room. Albizu suffered burns & seizures, ultimately passing from cancer as a result in 1965.

“Delbert Africa” 2003. Yasmin Hernandez. Mixed media on canvas. This image marks the moment in which Delbert Africa, member of the Philadelphia organization MOVE, steps out unarmed, hands in the air & is still beaten by the police during a raid of the MOVE home. A photograph of the incident is collaged on his chest as the sacred heart, his Christ-like image is bordered by a gold background. The collage includes other images from that horrific raid of the MOVE home in West Philadelphia on August 8, 1978 and of the 1985 bombing of the MOVE home by the police. Delbert Africa was a political prisoner for 42 years. He was finally released in 2020 and passed six months later. With this image I aim to visibilize an image largely eclipsed and hidden from US history.

“Obatala” 2003 Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. Commissioned by Alex Ulanov. Portrait of the Yoruba orisha of peace, wisdom, creativity: Obatala. Divine Masculine is the wise, peaceful energy of our elders and ancestors. It is achieving the experience and wisdom to speak from a confident space marked by inner knowing, inner peace, self-trust and self-love. Divine masculine is having the grace to listen, be touched and expanded by another’s experience.

"Portrait of the Artist & Her Brother in Warrior Training Camp" 2003. Yasmin Hernandez. Acrylic on canvas. I painted this image after a favorite family snap shot of my brother & I wearing boxing gloves when I was 5. I meant it as a tribute to my amazing big brother. He first saw it at an exhibit I opened on April 27th, 2003. On April 27th, 2010, 7 years to the day, we lost him to cancer. This portrait had been hanging in his room. Honor your loved ones however you can, now while you can tell them & show them. Let’s commit to lifting each other up, versus pulling others down into our misery. Let’s assume the responsibility of our healing so we cease dumping our pain and trauma on others. Let’s commit to being a safe, sanctuary space for ourselves and others so we can heal safely, collectively.